Innovative Antibody Testing Amidst the Pandemic

Written on

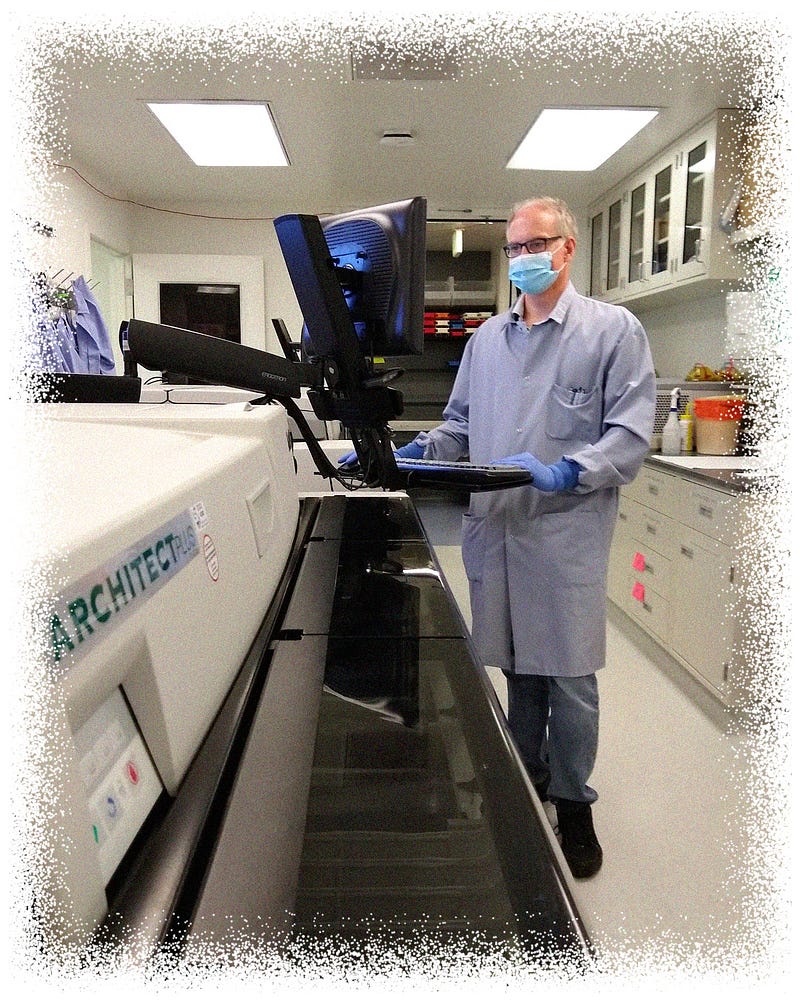

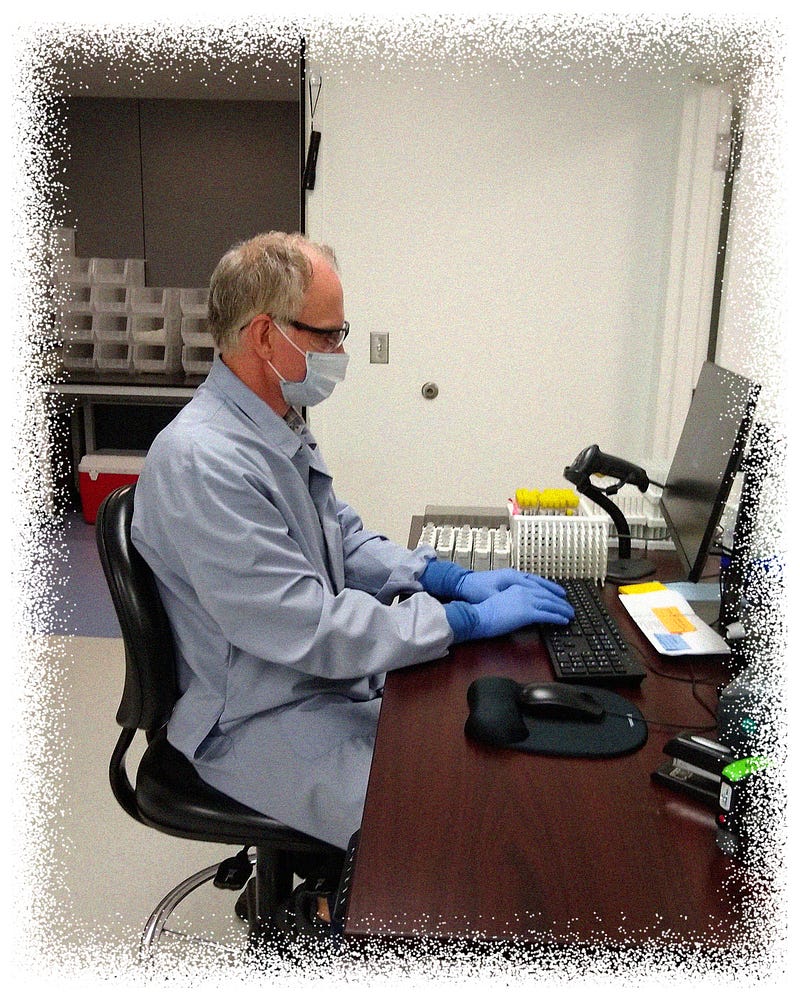

A Day in the Life of a Medical Laboratory Scientist

Meet Jason Hord, a dedicated medical laboratory scientist at the University of Washington’s Virology lab, working tirelessly to process antibody tests for COVID-19. His day begins around 10 a.m., waking up naturally as the sunlight filters into his bedroom. By this time, his wife has already left for work, and his two children are engaged in their online classes. Over the past couple of months, Hord has adjusted his sleeping and working hours to accommodate the demanding schedule of the lab, which operates around the clock to analyze samples for antibodies.

Recently, there's been growing attention on a new type of medical test that could aid in reopening the nation— the antibody test. This test analyzes blood samples to determine whether an individual has been infected with the coronavirus and has developed antibodies. Typically, the human immune system generates antibodies in response to foreign pathogens, potentially providing immunity against future infections. Therefore, a positive antibody test could suggest that a person is safe to return to work.

Despite the promise of these antibody tests, their reliability has been called into question. The American Medical Association has advised caution, warning that false positives—results indicating immunity where none exists—are a significant concern.

In early March, while many University of Washington staff were sent home, the Virology lab ramped up its operations to a 24/7 schedule. They were among the first academic labs in the U.S. authorized to perform diagnostic tests for the coronavirus. Hord works the evening shift from 4 p.m. to 12:30 a.m. In April, the lab had the opportunity to validate a coronavirus antibody test developed by Abbott Laboratories. If successful, this test could allow hospitals and patients to send samples to the University of Washington for analysis.

The lab had previously used the Abbott analyzer, known as The Architect, for hepatitis antibody testing, so transitioning to the coronavirus test was a natural progression. Hord and his colleagues conducted tests on 1,020 serum samples collected before the virus was known to be in the U.S., yielding only one false positive. This impressive result indicated that the Abbott test had a specificity of 99.6% and was 100% sensitive for samples taken at least 14 days post-symptom onset, as published in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

To maintain a balance between work and family, Hord starts his mornings with a 25-minute run. After returning home around 11 a.m., he enjoys a nutritious breakfast of cereal with yogurt, walnuts, and fresh fruit accompanied by coffee. The following hours involve him guiding his children through their schoolwork; his son is engrossed in video games while his daughter practices dance moves. They have a system in place, with Hord's wife checking in to ensure the kids stay on task.

As the clock nears 3:30 p.m., Hord heads to work. His commute has become quicker due to many people working from home. Upon arrival, he takes the elevator to the lab's third floor, where he finds a bustling environment as the day shift scientists wrap up their tasks. “The 4 p.m. shift is ideal,” he explains, as it allows him to identify unfinished tasks from the day before.

“I often think about those behind the scenes, as we don’t know their full stories,” Hord reflects.

By around 4:30 p.m., Hord is geared up in personal protective equipment, ready to analyze patient samples for antibodies. He meticulously prepares the testing equipment and initiates control tests—samples known to either contain or lack the virus. Once confirmed, he loads batches of 25 samples into The Architect, which takes about 30 minutes to process each one.

For the next couple of hours, Hord alternates between multiple analyzers, processing thousands of samples daily. He remains focused, with no time for distractions. Throughout this period, bells signal the arrival of new sample shipments, emphasizing the importance of teamwork in managing the influx of tests.

At 6:30 p.m., Hord takes a break for dinner. Initially, the lab encouraged scientists to bring meals, but local donations have significantly supplemented their food supply. Community efforts have provided various meals, supporting local restaurants while feeding frontline workers. Hord describes the variety: “We’ve had Thai, Italian, and breakfast foods—it’s been fantastic.”

After a brief dinner, he returns to the lab for more testing. Hord often steps outside for a quick breather, appreciating the quiet streets. However, his breaks are short-lived; he swiftly returns to his responsibilities.

As 10 p.m. approaches, fatigue sets in. Hord knows it’s time to keep moving. He visits the break room, where the aroma of coffee lingers, but he resists the temptation, mindful of the late hour. After a quick chat with colleagues, he resumes his testing duties until midnight.

As his shift winds down, Hord enjoys the little things, like spotting rabbits outside—an unexpected joy during these times. He scrolls through his phone, catching up on the news while preparing the lab for the overnight staff.

By 12:30 a.m., Hord heads home, arriving around 1 a.m. and settling in for a few hours of sleep. Hord finds purpose in his work, knowing that each sample carries a story. “I worry about the people behind those samples,” he admits, highlighting the unseen impact of his role.

Although he acknowledges the importance of the antibody tests, Hord believes the expectations may be unrealistic. He trusts the accuracy of the tests he's conducting, but notes that only about 2% of the general population has developed antibodies to the virus. “What does that really tell us?” he wonders. While the test informs about past infections, the uncertainty surrounding re-infection and the protective nature of antibodies adds to the complexity of the situation. “With so few positives, it’s clear that most of us remain vulnerable to infection, so concern is warranted,” he concludes.

This video discusses how Canadian scientists developed a rapid COVID-19 antibody test using a firefly enzyme, showcasing innovations in testing technology.

In this episode of the Joe Rogan Experience, renowned epidemiologist Michael Osterholm shares insights on the pandemic, antibody testing, and public health strategies.