Rethinking Nefertiti: New Perspectives on an Icon of Beauty

Written on

Chapter 1: The Enigmatic Queen Nefertiti

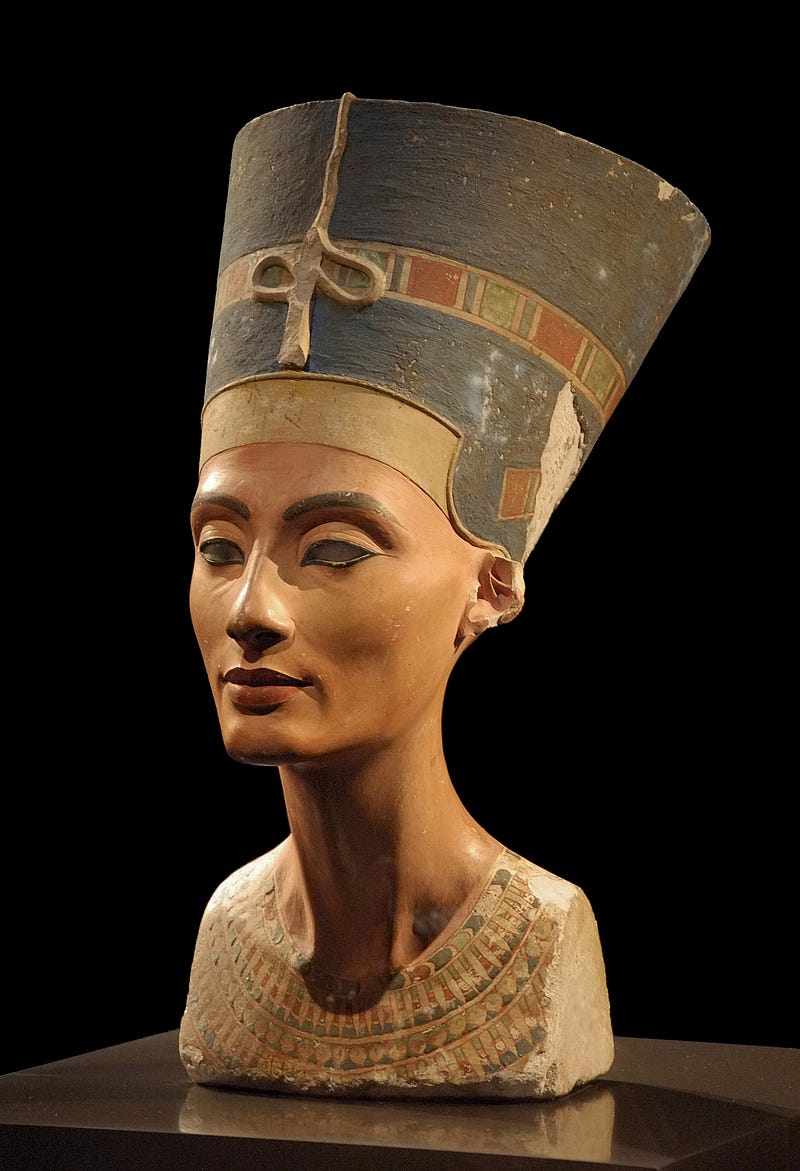

Nefertiti has long been celebrated as a symbol of beauty, with her famous bust, often dubbed the ‘Berlin Mona Lisa,’ residing in Germany for over a century. Recent discoveries, however, prompt us to rethink our conventional view of her appearance.

[Photo: Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons] Nefertiti, who lived around 1380–1340 BC, was the spouse of Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, also known as Akhenaten. Her name translates to ‘The Beautiful One Has Come,’ though her origins remain uncertain, with some theories suggesting she may not have been Egyptian—a claim that has yet to be conclusively proven.

Section 1.1: Challenging Conventional Beauty Standards

Numerous publications have lauded her extraordinary beauty, largely based on the renowned Berlin bust. Yet, Egyptian archaeologist Prof. Tarek S. Tawfik recently published findings in the ‘Journal of the Faculty of Archaeology’ at Cairo University, which challenge this narrative.

The artistic conventions of the time underwent a significant shift with Akhenaten's rise to power. Unlike previous depictions, the royal family began to be represented in a hyper-realistic fashion. Features such as sagging jaws, visible skin folds, wide hips, and prominent abdomens became commonplace.

Interestingly, the elongated skulls of princesses and narrow eyes were also characteristic of this period. This contrasts starkly with earlier Egyptian art, where rulers were depicted in an idealized manner—youthful, with broad shoulders and smooth features, reflecting an image of eternal youth.

Section 1.2: A Shift in Artistic Representation

The reason behind this transformation in artistic style remains uncertain. It’s possible that Akhenaten sought to portray himself authentically, despite any health issues he may have faced. However, this new style was short-lived; following his death, traditional artistic practices quickly resumed.

[Photo: Philip Pikart, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Chapter 2: The Evolution of Female Beauty Standards in Ancient Egypt

What qualities did ancient Egyptians find attractive in women? Despite the millennia that separate us from that civilization, we can identify changing ideals of beauty. During Akhenaten's rule, these standards evolved once again.

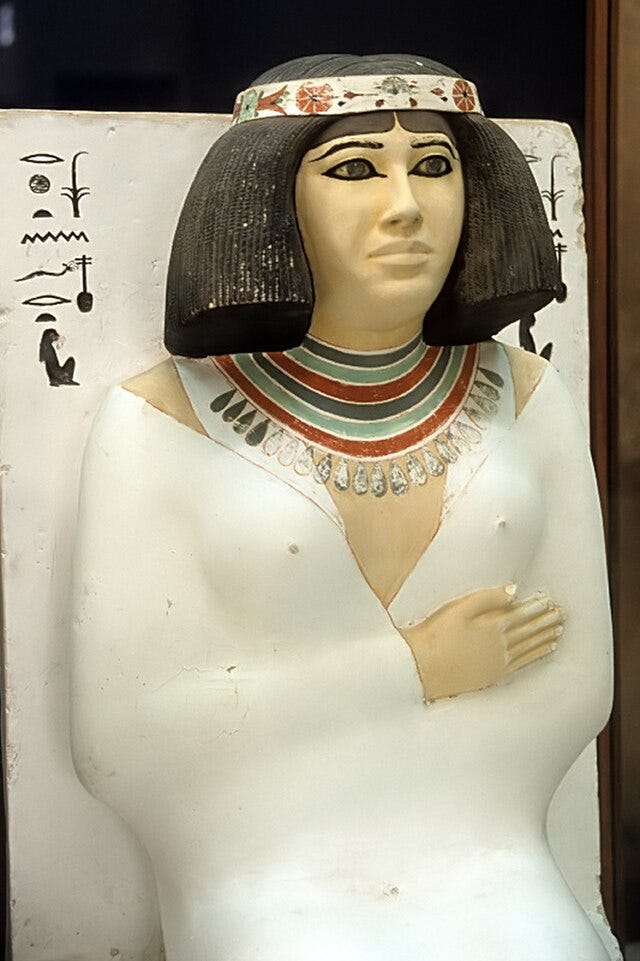

Prior to this era, women with fuller faces, prominent cheekbones, large eyes, and thick necks were deemed beautiful. This ideal was consistently reflected in the portrayals of royal women and goddesses throughout Egyptian history, including the prominent female pharaoh Hatshepsut.

However, the bust of Nefertiti diverges from these established norms. Her features are elongated and thin, with high cheekbones, a long neck, and relatively small, narrow eyes. Visible veins on her neck and subtle signs of aging suggest a more mature appearance, contradicting the traditional ideals of beauty celebrated in previous eras.

The next example of Egyptian beauty can be seen in Nofret, whose name means "beautiful." [Photo: Roland Unger, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Was Nefertiti truly beautiful?

The answer is complex. Beauty is subjective and varies across cultures and eras. Prof. Tawfik states that regardless of whether Nefertiti was genuinely beautiful, the portrayal in the Berlin bust does not align with the beauty standards of royal women from earlier periods.

This bust, celebrated today, may simply reflect a unique artistic choice rather than a true representation of Nefertiti. It resonates with contemporary standards of beauty, particularly those prevalent in the Western world.

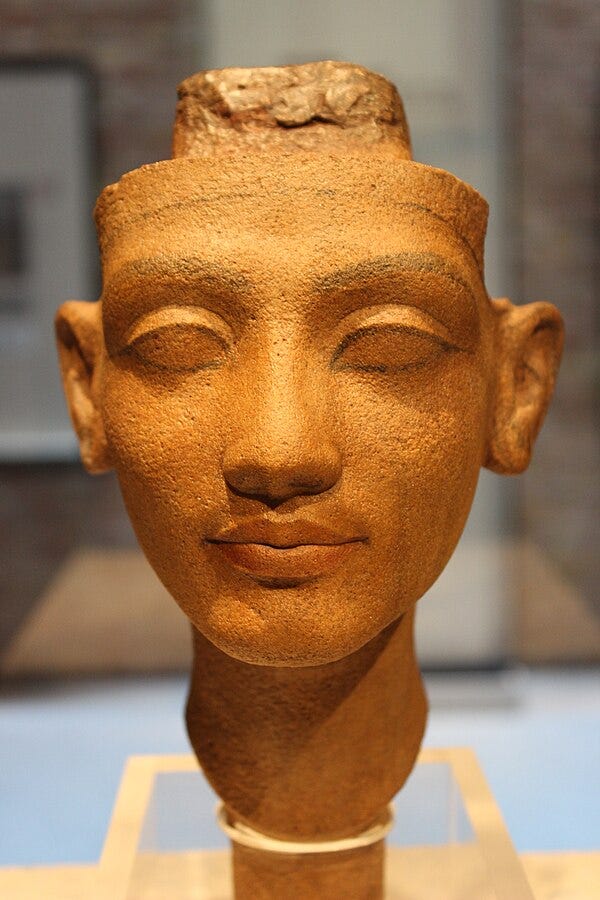

[Photo: Pries, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Section 2.1: The Return to Traditional Beauty Ideals

The radical shift in female beauty ideals during Akhenaten's reign was short-lived. Successors quickly reverted to the previous standards, favoring thick necks, fuller faces, rounded cheeks, and large eyes. These characteristics would dominate representations of beauty in ancient Egypt until the civilization's decline and beyond.