Seven Notorious Hoaxes That Deceived the Global Public

Written on

Chapter 1: The Craft of Deception

Throughout history, various hoaxes have captured the imagination of the public, demonstrating the ease with which misinformation can spread. Here, we delve into seven notable examples that left a lasting impact.

Section 1.1: A Fabricated History

In 1917, journalist H. L. Mencken authored an article titled “A Neglected Anniversary” for the Evening Mail. In it, he lamented that Americans had overlooked the 75th anniversary of the modern bathtub's invention. Mencken concocted a series of elaborate claims regarding the bathtub's origins, asserting it was created in Cincinnati and that baths were once prohibited due to doctors' misguided fears about their safety.

Mencken’s goal was to illustrate the gullibility of the American populace. Unfortunately, his lesson proved too effective, as even after revealing the truth, his fabricated account continued to circulate, appearing in numerous newspapers and references. It appears Mencken's insight into public credulity was spot on.

Section 1.2: Extraterrestrial Panic

Orson Welles orchestrated one of the most significant hoaxes in American history when he adapted H. G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds” for radio. The broadcast aired on October 30, 1938, and was formatted as a realistic news report. Although a disclaimer indicated that the events were fictional, it was only mentioned at the start and not repeated.

Most listeners tuned in after the disclaimer, leading them to believe the invasion was real. The realism of the adaptation incited widespread panic, particularly in regions where the fictional attack was purported to occur. The Federal Communications Commission later investigated the incident but concluded no laws had been violated.

The first video titled "10 Biggest Hoaxes That Fooled The World" explores numerous historical deceptions, including this infamous broadcast.

Chapter 2: The Search for Truth

Section 2.1: The Piltdown Man

In 1912, amateur fossil hunter Charles Dawson unearthed what he claimed to be the remains of a missing evolutionary link—a humanoid skull with an ape-like jaw—near Piltdown, Sussex. Initially believed to be 500,000 years old, this discovery was later found to be a forgery when scientists analyzed the remains in the 1950s, revealing that the human skull was only about 50,000 years old and the jawbone was much younger. It was determined that Dawson had intentionally planted the fossils.

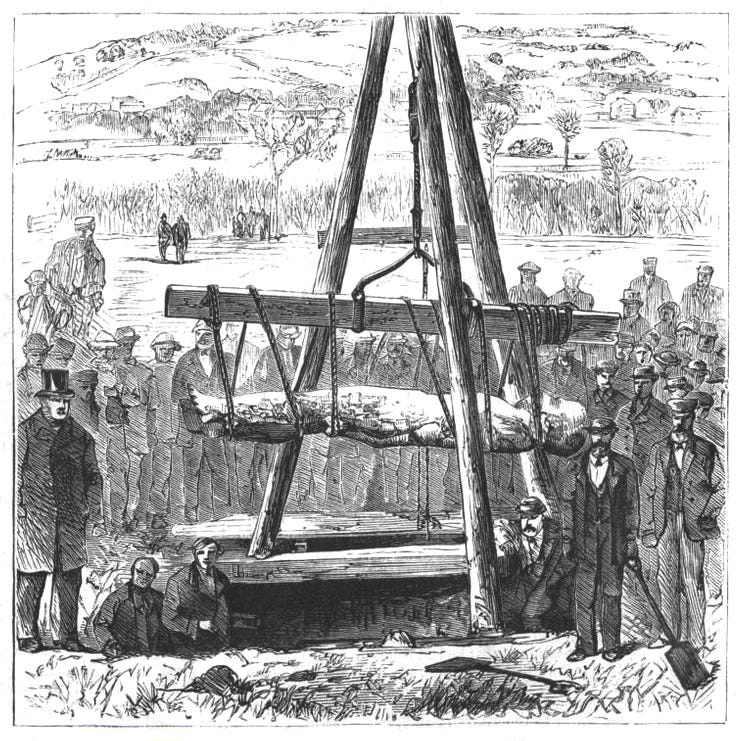

Section 2.2: The Cardiff Giant

In 1869, workers digging a well stumbled upon what appeared to be a petrified 10-foot tall man. Dubbed the Cardiff Giant, this discovery was hailed by some as proof of biblical giants. However, it was ultimately revealed to be an elaborate prank orchestrated by cigar manufacturer George Hull. Hull had hired sculptors to create the statue from gypsum and buried it, leading to its sensational discovery.

Section 2.3: The Alien Autopsy Hoax

In 1995, Ray Santilli claimed to have footage of an alien autopsy, purportedly obtained from a retired military cameraman. The video captivated the public for years until Santilli admitted in 2006 that it was a recreation of damaged original footage. Despite his admission, the initial excitement surrounding the video highlighted the public's fascination with extraterrestrial life.

The second video, "The Top 10 Greatest Hoaxes of All Time," discusses various hoaxes, including the infamous alien autopsy footage.

Section 2.4: The Archaeoraptor

In 1999, National Geographic announced the discovery of a feathered dinosaur fossil, the Archaeoraptor, which was thought to fill a crucial gap in the evolutionary history linking birds to dinosaurs. However, this discovery was soon debunked as a composite of unrelated fossils, falsely created to increase its market value. The fraud was so significant that it earned the nickname "Piltdown Bird," echoing another historical hoax.

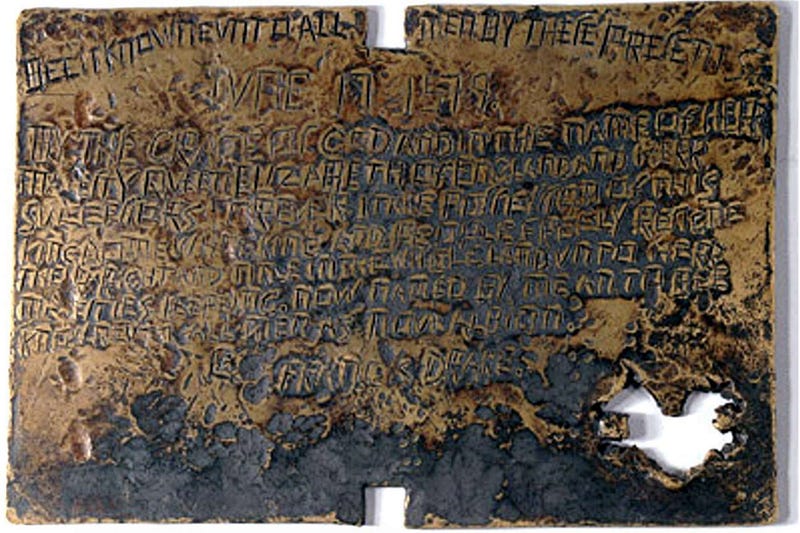

Section 2.5: Drake’s Plate

Discovered in Northern California in 1936, Drake’s Plate was believed to be a brass marker left by Sir Francis Drake during his 1579 expedition. It gained worldwide attention and was featured in textbooks, until investigations revealed it was a modern creation. The hoaxers, friends of the historian Herbert Bolton who had authenticated it, revealed the truth in 2003, exposing Bolton's hasty purchase as a practical joke.

By examining these hoaxes, we can see how easily misinformation can take hold and how it often reflects societal beliefs and fascinations.