# The Fascinating Journey of the Flowerpot Parasol Fungus

Written on

Chapter 1: Unveiling the Flowerpot Parasol

The battle against the toadstools in my pots seems futile. Honestly, I'm not putting up much of a fight. It requires considerable effort to inspect the pots, don gloves—who knows if these fungi are harmful?—and extract the vibrant yellow forms as they sprout from the soil. While there's little benefit in removing them, observing their sudden emergence is rewarding.

But these fungi don’t simply materialize out of nowhere.

Q: So, from where do these fungi originate?

A: They seem to appear from thin air.

The first documented instance of what we now call the Flowerpot Parasol (Leucocoprinus birnbaumii, Agaricaceae) dates back to 1785. Mycologist John Bolton described this species in his 1788 work, An History of Fungusses, Growing about Halifax, referring to it as the Yellow Cottony Agaric. He noted that the specimen he documented grew among bark in a greenhouse owned by J. Caygill, a prominent Yorkshire merchant.

This ‘pine-stove’ was a hothouse meant for cultivating pineapples—a luxury item in Georgian times, symbolizing wealth and status.

The first video titled "How to Understand the Different Colors of Gold" explores the various hues of gold, drawing parallels to the vibrant colors of fungi, including the Flowerpot Parasol.

Pineapples didn't make their way directly from the Americas to the Georgian elite's hothouses; they took a longer path.

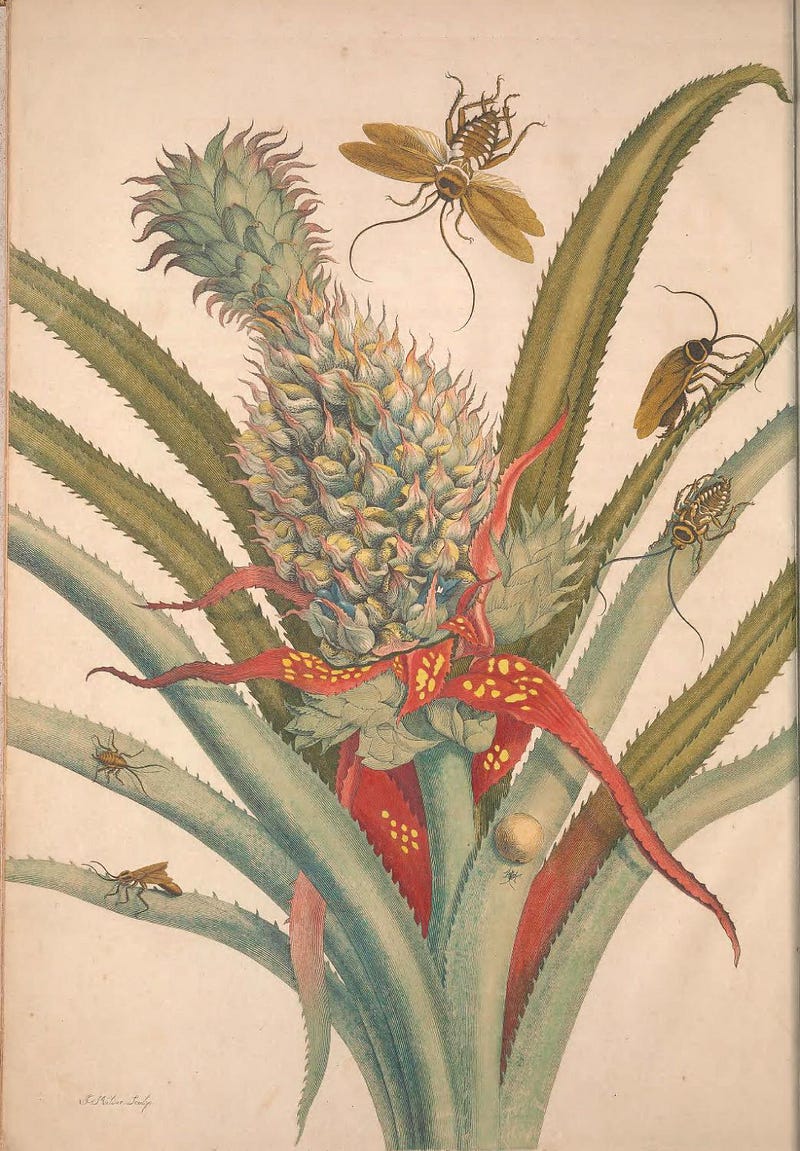

Illustration of a pineapple from Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium (1705) by Maria Sibylla Merian. Public Domain.

To answer the question: where do these fungi come from? They begin as tiny spores, often imperceptible to the naked eye. Carried by the wind, these spores land on nutrient-rich, moist soil. Fine threads of mycelia develop, intertwining to form a complex network that secretes enzymes to decompose organic matter, providing essential nutrients. For most of their lives, these fungi remain unnoticed, only to reveal their stunning yellow umbrellas in the sunlight for a brief moment.

A close-up view of the gills of a Flowerpot Parasol toadstool. © Bronwen Scott.

Section 1.1: Pineapples and Their Journey to Europe

The Hortus Kewensis is a comprehensive record of the plants cultivated at the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew. The first edition, published in 1768, catalogs 2,700 species, detailing their introduction to the collection. According to this record, the pineapple was brought to the garden in 1690 by William Bentinck, Earl of Portland, a Dutch diplomat and close associate of William III.

Bentinck was known for his exceptional garden filled with exotic species, rivaling those of other Dutch nobility. The Dutch were adept at cultivating rare plants, sourcing numerous species from their colonies across the globe. The Hortus Botanicus in Leiden, established in 1590, predated Bentinck's introduction of the pineapple by a century, although the fruit itself had been brought to Spain from Guadeloupe by Christopher Columbus.

Once in Europe, pineapples struggled to thrive until Agneta Block created an ideal environment in a hothouse near Amsterdam in 1687, leading to a surge of hothouse gardening across Europe.

The second video titled "A Guide to Different Types of Gold" provides an overview of the various kinds of gold, inviting viewers to explore their unique characteristics, much like the diverse world of fungi.

Section 1.2: The Evolution of Scientific Classification

The scientific classification of the Flowerpot Parasol has evolved over time, shifting from Agaricus to Lepiota to its current designation, Leucocoprinus, amidst a plethora of misidentifications. Despite these changes, the vivid colors—described as aurea (golden), lutea (yellow), and flos sulphurina (flowers of sulphur)—and its affinity for hothouse environments make it relatively easy to trace through literature.

In 1839, August Corda discovered the fungus in greenhouses in Prague and named it Agaricus birnbaumii, noting its prevalence among pineapple plants in Count Salm’s garden.

More than three centuries passed between the pineapple's arrival in Europe and the Flowerpot Parasol's first documentation. However, the time between the establishment of hothouses and the first record of the fungus is much shorter. It appears that this tropical fungus requires specific conditions to thrive, similar to the pineapple.

As houseplants gained popularity, the Flowerpot Parasol began appearing in various settings, no longer confined to the estates of the elite. Mycologist Paul Christoph Hennings noted its presence in 1898, mistakenly identifying it as a white species, Lepiota cepaestipes, in the cactus garden of Heinrich Hildmann in Birkenwerder.

It starts with invisible spores—or a sprinkle of yellow, reminiscent of gold dust in a prospector’s pan. Uniquely, the Flowerpot Parasol produces sclerotia—a dormant stage of mycelia wrapped around food reserves. Although these sclerotia are tiny, their abundance can create the illusion of a yellow mold overtaking the plant pot. They can survive for years, awaiting the perfect conditions to flourish.

The journey of the Flowerpot Parasol takes it from Georgian hothouses to tropical rainforests in Far North Queensland, where the climate allows it to thrive beyond glass confines, transforming idle curiosity into profound knowledge.

The same toadstools featured earlier, captured just one day later. © Bronwen Scott.