Exploring Free Will through Scientific Metaphysics

Written on

The common narrative surrounding free will posits that if one subscribes to naturalism—rejecting divine entities—and takes the principles of cause and effect seriously, then free will must be an illusion. However, can this narrative withstand critical examination? To investigate, we will delve into the concluding chapter of Scientific Metaphysics, edited by Don Ross, James Ladyman, and Harold Kincaid, which aims to provide an alternative to the analytic metaphysics that has produced concepts like philosophical zombies and panpsychism. (Refer to parts one, two, three, and four of this series.)

The chapter titled “Causation, Free Will, and Naturalism” is authored by Jenann Ismael, who is currently affiliated with Columbia University. Although Ismael's discussion centers on free will in the framework of Newtonian physics, her arguments hold true within the contexts of General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics as well.

Ismael argues that the free will dilemma arises because, theoretically, the laws of nature could allow us to predict our actions if we knew the initial conditions of the universe. The fact that we lack knowledge about those conditions does not alter the core argument. Interestingly, this reasoning mirrors that of various philosophical figures, such as Sam Harris, Lawrence Krauss, or Jerry Coyne, who often discuss free will without a comprehensive understanding of the subject.

Ismael emphasizes that scientific insights into causality fundamentally challenge the everyday or "folk" understanding of the concept, making discussions about free will much more nuanced and the conclusions less definitive. Her chapter illustrates the shift from analytic metaphysics—which relies on common-sense notions—to scientific metaphysics, where concepts are derived from empirical scientific practice.

To begin, Ismael provides a brief history of causation. A basic understanding of causality is crucial for survival, as discerning cause-effect relationships can mean the difference between life and death. Science itself can be viewed as a method for systematizing our comprehension of cause-effect relationships, which are applicable to numerous scientific inquiries.

However, with Newton's introduction of physical laws, the connection between cause and effect became less straightforward. In physics, laws are expressed as differential equations that depict how certain quantities change over time. For instance, consider Newton's second law of motion:

F = m a

Here, F represents force, m denotes mass, and a signifies acceleration. Understanding this law does not necessitate any discussion of causation, nor is such a notion integral to its application. Notably, the relationship among the three variables in this equation is symmetrical. Causal discussions imply a temporal asymmetry, where causes precede effects, a characteristic absent in dynamical laws like Newton's. Ismael quotes:

> “Dynamical laws are what are sometimes called regularities of motion that relate the state of the world at one time to its state at others, but there is no direction of determination.” (p. 211)

While fixing earlier states determines subsequent states of the same system, the reverse is equally valid: one can establish earlier states from later ones, indicating complete symmetry. This notion prompted philosopher Bertrand Russell to critique the entire concept of causation as being pre-scientific:

> “The law of causality, I believe, like much that passes muster among philosophers, is a relic of a bygone age, surviving, like the monarchy, only because it is erroneously supposed to do no harm.” (Russell 1918: 180, cited in Ismael, p. 212)

Russell's view on monarchy may hold true, yet his dismissal of causation lacks nuance. Nancy Cartwright offered a compelling critique of Russell's stance, arguing that dynamical laws cannot replace causal understanding in scientific contexts since they lack the necessary information for manipulating physical systems.

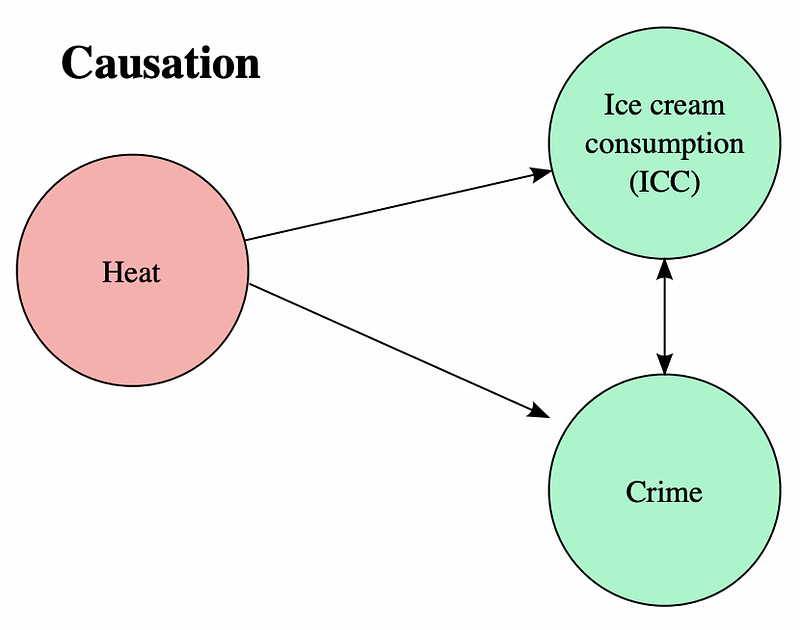

For instance, while it is a matter of physical law that there exists a strong correlation between bad breath and cancer—attributable to smoking—the converse is not valid; bad breath does not cause cancer—smoking does. Relying solely on dynamical laws would obscure the critical distinction between correlation and causation, which is crucial to avoid misguided interventions.

Another way to differentiate these concepts is that dynamical laws predict a system's state at one point based on its state at another, while causation allows us to act on the system to achieve desired outcomes (such as preventing cancer).

Philosophers often adopt an interventionist perspective on causation, positing that a system's causal structure encodes information about the results of hypothetical interventions. This leads to an understanding of causality through counterfactual scenarios: “if... then” propositions. In reality, individual variables are intertwined within a broader web of cause-effect relations, influenced by our choices regarding what to focus on or manipulate.

To illustrate, consider a drunk driver in a car accident. It is intuitive to assert that the driver caused the accident, primarily due to the decision to drink and drive. However, numerous co-causes were necessary, including the other driver's actions, the slippery road conditions, and the rain that made the pavement slick. Our focus on human agency, particularly the drinking decision, leads to the conclusion that it was the cause. This focus is not arbitrary; it is shaped by the causal web involved. A Martian might interpret the same event differently, yet that perspective would remain valid, provided it aligns with the underlying facts and causal relationships.

Ismael notes that the interventionist account of causality has a significantly richer modal structure than the account provided by dynamical laws. Modal logic examines necessary and contingent truths, such as “it is necessary that” or “it is possible that.” While dynamical laws illustrate how overall history changes with varying initial conditions, they remain silent about the implications of changes in local parameters of a specific system at a given time. Thus, causal laws offer less modal richness than causal accounts.

Crucially, Ismael asserts that there is no logical conflict between dynamical laws and interventional counterfactuals; they simply describe phenomena at different levels and with varying detail. While we cannot formulate a comprehensive causal-counterfactual model of the entire universe, we can effectively understand the universe's general behavior through dynamical laws. Conversely, dynamical laws do not elucidate the relationship between smoking and cancer or drinking and driving, whereas localized counterfactual models provide significant insights. As Ismael states:

> “For (almost) any set of global dynamical equations involving two or more variables, there will be multiple conflicting accounts of the causal structure of the system that satisfy the equations. These models will preserve the relations among the values of parameters entailed by the laws, but disagree over the results of hypothetical interventions.” (p. 215)

This illustrates how the concept of “free will,” viewed as part of the cause-effect web that emphasizes human agency, can coexist with the deterministic laws of physics. Choices regarding smoking and cancer, or drinking and driving, represent counterfactuals that do not contravene dynamical laws, yet they involve distinct local developments that necessitate an understanding of causality. Ismael further elaborates:

> “It was a remarkable discovery when Newton found dynamical laws expressible as differential equations that make the state of the universe as a whole at one time in principle predictable from complete knowledge of its state at any given time. But those laws are of little use to us, either for prediction or for intervention. We don’t encounter the universe as a unit. Or rather, we don’t encounter it at all. We only encounter open subsystems of the universe and we act on them in ways that require working [i.e., causal] knowledge of their parts.” (p. 220)

In essence, the universe presents itself not as a whole entity but rather as a collection of subsystems. The boundaries of these subsystems are influenced by human interests rather than dictated by natural laws. Our understanding of a specific subsystem hinges on our goals, leading to multiple models of a given system, all compatible with the dynamical laws and revealing different aspects of its causal structure.

Typically, we hold the past constant while allowing the future to vary, driven by our need to predict future states of a subsystem, which is motivated by our desire for actionable guidance. This indicates that the asymmetry between cause and effect is, in some respects, a result of our variable choices. What, then, is the connection between causal reasoning and free will? Ismael posits:

> “Causal thinking is a tool, a cognitive strategy that exploits the network of relatively fixed connections among the components of a system for strategic action, not a coercive force built into the fabric of nature that imbues some events with the power to bring about others. Far from undermining freedom, the existence of causal pathways is what creates space for the emergence of will because it opens up the space for effective choice.” (pp. 230–231)

Ultimately, our concern lies with human will—the capacity to make choices, to follow different paths based on our processing of available information in a given scenario. This information encompasses factual elements and our values, which influence our decision-making priorities.

Does Ismael’s scientific metaphysical analysis align with the folk understanding of free will? Not precisely, highlighting the divergence between analytic and scientific metaphysics. Analytic metaphysicians seek to maintain pre-theoretic views, while scientific metaphysicians argue that if scientific findings conflict with pre-theoretic concepts, the latter should be reconsidered. Ismael concludes:

> “The theory of general relativity doesn’t preserve pre-theoretic intuitions about space and time, but so much the worse for those intuitions. Someone looking to preserve pre-theoretic ideas will find little satisfaction in science.” (p. 233)

Ismael's chapter exemplifies what it means to engage in scientific metaphysics: rejecting the notion that metaphysics can exist independently of science. Sound metaphysics must incorporate relevant scientific information to address philosophical inquiries effectively; otherwise, it becomes a futile exercise.