<Title: Birds in Rocky Mountain National Park Face Urgent Adaptation Challenges>

Written on

Birds that rely on specialized ecosystems in Rocky Mountain National Park are under pressure to adapt swiftly to changing conditions.

Call to Action

“Over there, a brown-capped rosy finch,” Scott Rashid called to me as I struggled with my winter gloves and activated my phone to record the sighting. As a newcomer to bird counting, my role was to track every observation.

Rashid, a self-taught ornithologist, organizes the annual Christmas Bird Count in Estes Park. This local initiative, which surveys the highest national park in the U.S., has been a volunteer-driven effort for more than 70 years.

On the first Saturday of 2020, dressed in camouflage and a fur hat, Rashid briefed a group of over twenty volunteers gathered at the Estes Park Visitor Center. As the volunteers dispersed to their designated areas, I followed Rashid to his Jeep, eager to experience birdwatching alongside an expert. Standing by as he cleared space in the vehicle, I watched him toss aside books and retrieve a deceased rabbit, which he tossed into the trunk.

“Rabbits are beneficial for my bird boxes because their skin deteriorates easily,” he explained about the roadkill he had gathered that morning.

Having banded over 56,000 birds over the decades, Rashid has tracked individual birds from the Canadian Rockies to his own backyard. He uses the carcasses he finds around town to attract birds to his boxes, allowing him to monitor their movements and understand their habits.

Bird counts and banding efforts reveal that birds serve as excellent indicators of ecological disruptions. Their visibility over time and sensitivity to environmental changes make their migrations a critical focus for researchers.

Data from 119 years of bird count observations across thousands of locations have produced an impressive dataset that has supported more than 200 peer-reviewed studies. A recent analysis by the Audubon Society, in collaboration with the National Park Service, projects that significant shifts in bird populations are anticipated in the coming decades. By 2050, one-quarter of all birds in national parks may be replaced by different species. While some will relocate, others may face extinction due to a lack of alternative habitats.

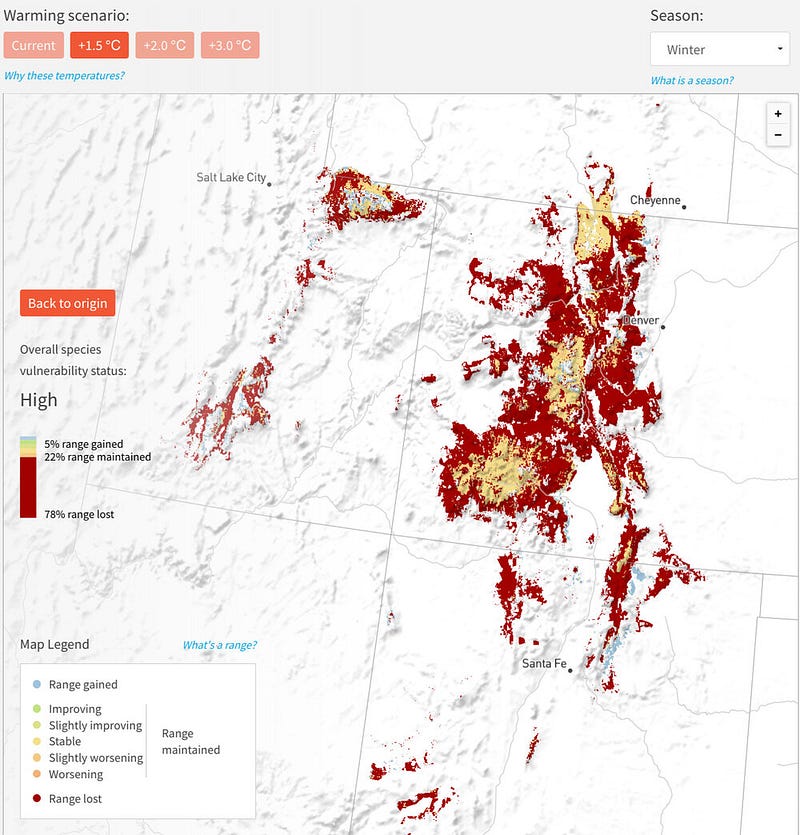

The Audubon study combined climate models with Christmas Bird Count data, the longest-running citizen science project in the U.S. It indicated that at least ten bird species may struggle to survive in RMNP, including Colorado’s state bird, the Lark Bunting.

Among the bird species currently found in RMNP, climate conditions in summer under high-emission scenarios are expected to improve for 68 species, remain stable for 34, and worsen for 20. Nine species may lose their suitable climate entirely in summer, potentially leading to their local extinction. This information is derived from the Birds and Climate Change: Rocky Mountain National Park study published by the National Audubon Society in March 2018.

On a positive note, over 30 species displaced from other regions are likely to find refuge in the park, particularly during winter as conditions become milder. Researchers caution, however, that their models do not account for the intricate dynamics beyond climate change, such as species interactions that introduce further uncertainty.

Birds have historically survived through adaptation, as evidenced over 80 million years of evolution. However, the current circumstances are unprecedented. As they continue their northward migrations since the last glacial period, birds now face a rapidly warming planet alongside human-induced pressures that threaten the ecosystems they rely on.

Human activities are severing migration corridors, damaging delicate tundra, and polluting the atmosphere. These combined factors raise concerns among ornithologists about which species will adapt quickly enough to navigate the extensive changes.

While some species thrive under warming conditions, expanding their ranges into increasingly hospitable areas, others, particularly those in high-altitude habitats like RMNP, are confronting diminishing tundra ecosystems.

The alpine tundra, covering one-third of RMNP's 265,761 acres, is a defining feature for many visitors. They can traverse Trail Ridge Road, one of the highest paved routes in the nation, to experience this landscape from their vehicles — at least for now. Ecologists predict that as the climate continues to warm, grasses and shrubs will encroach upon this habitat, pushing montane ecosystems upward.

“Montane habitats are moving higher up the mountains, but there’s only so far they can go before disappearing,” stated Garth Spellman, Curator of Ornithology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

The Brown-Capped Rosy Finch is an endangered species limited to areas above the treeline. This alpine ecosystem is being pressured from below by encroaching lower-elevation habitats. Concerns are rising over the genetic diversity of this species, as its limited geographic range may hinder its ability to adapt through interbreeding.

The Clark’s Nutcracker plays a crucial role in the forest ecosystem by caching tens of thousands of seeds annually, many of which remain unreturned, giving them a chance to germinate. However, changing climate conditions are promoting a fungus that threatens Limber pines, which would subsequently compromise the nutcracker’s food supply. Researchers anticipate a 40% loss in Limber pine coverage over the next decade.

Genetic Diversity is Key to Survival

With an ornithology collection housing over 50,000 specimens, Spellman has direct access to DNA from birds spanning the early 1800s to the present. He can easily retrieve data from extinct species, such as the passenger pigeon, which vanished due to overhunting in 1914.

While sitting in the museum's lounge, watching flocks of Canadian geese in a nearby meadow, we discussed Spellman’s research into the genetic profiles of bird species since the last glacial maximum.

Examining the entire migratory range of a species, like the geese traveling from central Mexico to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, reveals that not all individuals migrate the full distance. There are subgroups within species that possess unique genetic traits suited to different habitats. This genetic diversity is crucial for a species' survival.

According to Spellman, genetics can illuminate minor differences among subgroups, enhancing our understanding of how adaptable a species might be to climate fluctuations. More subgroups translate to greater genetic diversity, which in turn strengthens a species' resilience.

“Interbreeding with other species is crucial for their evolutionary history,” noted Spellman. “This influx of variation is vital for generating diversity.”

He emphasized that birds in northern latitudes have had limited time for interbreeding, having only recently gained access to these areas since the last ice age. This limited genetic diversity is evident when comparing their DNA to subgroups of the same species near the Equator, known as the leading edge effect. Subgroups extending the range boundary, like many birds today, often display less diversity than those in the broader range.

High-elevation species, such as the brown-capped rosy finch and the white-tailed ptarmigan, are particularly vulnerable to climate change due to their restricted ranges and potential genetic limitations. RMNP provides a sanctuary for these unique species, but climate models indicate that their habitats are rapidly diminishing.

Spellman is involved in the first genetic sequencing project for the rosy finch, aiming to assess the species' diversity and vulnerability in the future, suspecting that undiscovered subgroups may exist.

Challenges of Species Protection

National park managers across the country are grappling with the gradual ecological changes that have unfolded over recent decades. Koren Nydick, chief of resource stewardship at RMNP, highlights human-induced stressors such as air pollution and increasing visitor numbers as chronic challenges.

“When considering climate change, we must remember the multitude of other stressors already impacting the park,” she remarked.

Because national park service lands are well-protected, they serve as refuges for birds and other species vulnerable to shifting conditions. The pressing question remains: can park managers take effective measures to safeguard these species?

According to the Audubon study, even under conservative warming scenarios reaching +1.5 degrees, the rosy finch is projected to lose its entire summer habitat and most of its winter habitat due to the consequences of early spring heatwaves. The white-tailed ptarmigan faces a similar struggle, and a 2006 study underscored the immense challenges conservationists face in protecting this species.

This study indicates that managing ptarmigan populations will necessitate safeguarding their alpine habitat from overuse, recreation, mining, and broader environmental disturbances contributing to global change, such as pollution and ozone depletion.

Essentially, removing human impact is crucial for species survival.

In her earlier career at the Mountain Studies Institute, Nydick examined how toxic air pollution affects high-elevation lakes, particularly from dairy farming ammonia emissions. She notes that the impact has escalated to the point where it is now visible without a microscope, as algae proliferate and threaten sensitive aquatic species, further depleting resources essential for bird survival.

No ecosystem remains untouched. Forests are also undergoing changes.

Scientists are addressing blister rust, a disease that has recently spread within the park, likely exacerbated by climate change. Warming conditions extend the active period for pathogens like the pine beetle, which has devastated Colorado's forests. In 2015, blister rust surged, resulting in the loss of 50 Limber pine trees, up from just one or two in previous years. Although not abundant, this keystone species significantly impacts biodiversity due to its highly nutritious seeds, which are more calorie-dense than chocolate.

After 50 years, a single Limber pine will produce one cone, and it takes a century to reach peak production. This species defines the Rocky Mountain treeline, capable of enduring extreme conditions.

The Limber pine relies heavily on the Clark’s Nutcracker, a small songbird regarded as an architect of the Rocky Mountain forest. This bird can store over 30,000 pine seeds in a season, many of which remain uneaten and can germinate. The nutcracker evaluates seeds by weight to determine their quality, digging out storage sites in snow-free areas where Limber pines thrive, demonstrating remarkable memory for its extensive caches.

While other animals also consume these seeds, only the nutcracker can disperse them widely. This symbiotic relationship is endangered if park managers fail to control the spread of blister rust and protect Limber pines as a food source.

Researchers like Laurel Sindewald, a Ph.D. student at Colorado State University studying the tree, dedicate their efforts to understanding the threats facing national park ecosystems. Sindewald warns that if Limber pines are eradicated from the park, it could force dependent species to relocate.

“Clark’s Nutcracker is a primary seed disperser. If Limber pine declines, the nutcracker might adapt to other pine sources or seek more abundant food elsewhere,” she explained.

This uncertainty looms over how birds will respond to climate change. How willing and capable are they of relocating to adapt?

Science Enables Conservation

“When I began my journey in ornithology, I was captivated by evolutionary history. Now, I’m focused on studying it to inform conservation efforts,” stated Spellman, who transitioned from academia to curating the science museum’s ornithology collection.

This sentiment resonates with many scientists.

“I am driven by the conservation of our natural resources,” remarked Sindewald, whose research examines climate change's effects on high-elevation forests. Her mentor, Diana Tomback, dedicated her career to studying whitebark pine trees, heavily impacted by blister rust in the northern Rockies and now classified as endangered. Tomback established the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation, advocating for funding to protect and restore the species.

As environmental conditions shift, scientists are often the first to witness the repercussions. Some observe changes in melting ice caps, others in coral bleaching, while many note subtle shifts in avian behaviors at locations like RMNP.

Park managers understand that the lands they oversee are vital havens for biodiversity. With scientists documenting evidence of change, they are positioned to make informed decisions about conservation strategies. Determining which species are most critical to protect and how to allocate resources is a complex task. Which species are federally protected? Which hold the most ecological importance? With increasingly limited resources, including funding cuts from government shutdowns and pandemics, managers must strategize effectively.

In the past, conservationists have harnessed emotional appeal to draw attention to urgent issues.

As we trudged through deep snow off the trail during the bird count, Rashid pointed out a distant cliff where researchers have managed a bald eagle nest following its drastic decline during the era known as Silent Spring.

During this period, named after Rachel Carson’s influential book that exposed the devastating effects of DDT on bird populations, the bald eagle became a powerful symbol of conservation, galvanizing public action. Fortunately, this momentum also benefited other bird species as society worked to regulate the harmful pesticide.

Unfortunately, even iconic species like the polar bear cannot address today’s complex issues. While scientists and conservationists strive to emphasize climate change's importance in reducing our carbon footprint, the myriad stresses on ecosystems exceed what simple solutions can resolve. Even without climate change, the existing pressures leave ecosystems vulnerable.

“Our climate change strategy involves minimizing other stressors as much as possible,” Nydick stated. “We have limited control over climate change, so we focus on mitigating other challenges and identifying crucial processes to buffer its impacts.”

With 265 bird species utilizing RMNP throughout the year, the avian community stands to lose significantly. The intricate connections between each bird and the ecosystem underscore the challenges park managers face in determining effective remedies. As animal distributions shift and ecosystems evolve, solutions may remain elusive.

At a recent science conference in Estes Park, researchers shared insights on ongoing initiatives, drawing a small but engaged audience eager to learn about the status of their cherished public lands.

Topics included elk-proof fencing to restore willows, strategies to combat blister rust and protect Limber pines, beaver reintroduction for wetland preservation, nitrogen management for air quality improvement, citizen science initiatives, interagency collaborations, and reminders to practice responsible recreation. Each strategy aims to bolster specific species or ecosystems against the impacts of climate change.

“If I were to place a bet, I would wager on even greater changes ahead,” asserted Scott Esser, Director of the Continental Divide Research and Learning Center, which organized the conference.

As Nydick pointed out, the capacity to mitigate climate change effects on the ground is limited. Even under the least severe scenarios, extinction rates will rise as habitats transform too rapidly. Eventually, the delicate tundra may vanish, and new species may take their place.

“If we were to revisit this area ten thousand years after climate change, the diversity we observe will be dramatically altered,” remarked Spellman. “We are witnessing the sixth mass extinction, and when species disappear at such a rapid pace, we lose critical genetic variation.”

Counting on the Present

Our bird counting route began at the Bridalveil Falls trailhead, covering just two miles in two hours and tallying around 320 birds. The process is not precise, often involving estimates like, “Let’s count that as five finches…make it ten.”

While a single bird counter's work may seem charming, when you consider the vast number of circles coordinated worldwide (a circle refers to an area led by someone like Rashid for the count), and aggregate this data over 119 years, it enables tracking migration patterns and population trends in places such as RMNP. For example, only one nutcracker was recorded in 1953, and just nine in 2009, before numbers surged to 170. This year-to-year variability highlights the importance of long-term observations in avian science.

At the conclusion of the day, our group identified 55 different species, slightly below the 79 species expected to find suitable winter habitats in the park. If the Audubon study forecasts are accurate, that number could rise to nearly 100 by mid-century.

Birdwatchers will face significant challenges ahead.